Summer 2021

Crowd control

various designers

Mark Holt

Sam Winston

W. A. Dwiggins

Dan Adams

Order

Jesse Reed

Hamish Smyth

Aldo Novarese

Spin

Tony Brook

Designers are making illustrated books through crowdfunding instead of traditional publishing methods. By John L. Walters

Like much else in publishing, crowdfunding books is all about hope, faith and money. As the disclaimer on the homepage of a crowdfunding site makes clear, in surprisingly blunt prose: ‘Backing isn’t buying. You’re supporting ambitious creative work.’ Almost anything can be crowdfunded – charities, legal campaigns that call governments to account, movies, performances, software, vinyl box sets, board games – and there are a huge number of online platforms that make it possible for people to support the organisation of their choice by pledging money, including ArtistShare, Patreon, GoFundMe and CrowdJustice. In return, supporters receive anything from a bookmark to a limited-edition print; from an exquisite design monograph to the intangible sensation of helping a deserving cause. Design book publishing is dominated by Kickstarter, though Indiegogo is preferred by some publishers, and Unbound and Volume are books-only platforms

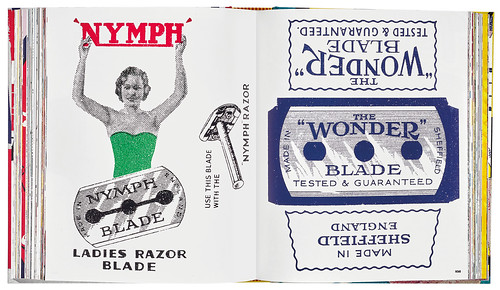

Spread from Andy Altmann’s lovingly assembled collection of what he calls Tat* – Inspirational Graphic Ephemera (Circa, 2021). Altmann defines ‘tat’ as ‘anything that looks cheap, is of low quality, or in bad condition; junk, rubbish, debris, detritus, crap.’

Top. Eight of the books mentioned in this feature.

Support for ambitious book projects, once the province of publishers, is increasingly in the hands of readers. And although the online tools used to garner support are relatively new, the process harks back to the subscription publishing models popular in the Victorian era and earlier. There have always been ventures (including this magazine) that have relied less upon hard-nosed investment than on readers prepared to pay in advance. Nevertheless, the fall in conventional publishing’s confidence in untested subject matter has given rise to a minor boom in crowdfunded books about visual culture, typography and graphic design, fuelled by the new means of reaching customers online: social media, newsletters, podcasts and other digital ‘word of mouth’ equivalents.

To get some understanding of this brave new world, I spoke to a number of people who are deeply involved in crowdfunded publishing. Unit Editions publishing director Patricia Finegan has been involved in crowdfunding since the imprint launched in 2009, and is generous with her hard-won advice. We spoke while she was working on Studio Culture Now, a survey of contemporary graphic designers and their studios. Crowdfunding is Unit’s preferred way of working. ‘It’s a way of reaching an audience that you can’t when you self-fund,’ says Finegan. ‘You get the opportunity to test the appetite of the potential readership.’ The last Unit book that was entirely ‘self-funded’ was Matt Pyke’s Universal Everything, which Finegan believes might have been even more successful as a crowdfunded project, since the process engages the audience in advance.

For David Jenkins of Circa Press, crowdfunding reflects the ‘present reality that illustrated books need funding.’ He compares the current situation to his time at Phaidon in the 1990s. ‘We asked architects to buy copies of their monographs, and we expected a gallery to support an artist, so it’s been a factor for a while.’ Unit’s Finegan is happy to work on hybrid projects such as Ed Fella – A Life in Images, out soon, which was partly supported by a Canadian Government SSHRC grant (administered by Toronto’s York University), which reduced pressure on the crowdfunding campaign. (It raised £56,297 of a £50,000 target via Kickstarter.)

Margot Atwell, Kickstarter’s director of outreach & international, has learned about crowdfunding from the inside. ‘You have to understand your audience and what they want in advance, which is really not possible in traditional publishing.’ How does Atwell think crowdfunding platforms have changed the world of publishing? Do authors need to learn new skillsets?

‘Crowdfunding represents a fundamental shift in the way things are bought and sold in the world today,’ says Atwell. ‘It used to be that a writer wrote, and a publisher helped them to get the word out. Traditional publicity channels – bookstore placement and other, older methods were effective and impactful.’ All that, she says, has changed.

Is the mainstream publishing industry changing in response to the popularity of crowdfunding? More than four years ago, Markus Dohle, Penguin Random House’s CEO, speaking at the Frankfurt Book Fair, said: ‘The fundamental challenge is moving from a BTB (business-to-business) oriented publishing industry to one that is BTC (business-to-consumer) oriented.’ He went on: ‘In an online world we publishers must establish direct connections with the reader.’

Thames & Hudson’s Volume imprint is a semi-detached branch of the publisher, started in 2017 by Darren Wall and in-house T&H editor Lucas Dietrich, stating that its aim is ‘to redefine the role of the publisher, and the relationship between creator and reader, to produce printed books of uncompromising standards for dedicated audiences.’ Volume’s website (Vol.co) presents a fascinating matrix of winners and losers: books by Anthony Burrill, Takenobu Igarashi and Liam Wong’s wildly overfunded TO:KY:OO (£140,698.67 pledged – original target £30,000) sit alongside unfunded titles such as Fvckrender’s Surrealista, and Self-Reliance: Thoughts for a New World, which is now coming out as a regular T&H book.

Atwell points out that, of 1.3m books published in the US in 2019, only 300,000 were published through traditional means. ‘The literal shelf space at bookstores is either staying the same or getting smaller,’ she says. ‘More and more publishers, and authors, are relying either on algorithms (such as Amazon’s or Google’s) to put their books in front of people … or direct relationships with readers.’

Steve Kroeter, founder and editor-in-chief of Designers & Books, was an early advocate for crowdfunded publishing, writing a short ‘white paper’ about it for a conference in 2017. His first project was a book about Ladislav Sutnar, followed by a successful campaign to reprint a facsimile of Fortunato Depero’s 1927 ‘bolted book’. Kroeter plans to launch four book projects in 2021, the first of which, a book of drawings by architect Louis I. Kahn, beat its $124,000 target in March 2021. I asked Kroeter whether there was a certain kind of design book that worked better than others, or was it more a matter of getting the numbers right?

‘The key to a successful crowdfunder is primarily being able to access a large list of potential backers by email,’ answered Kroeter. ‘Publicity and media attention help – but having a solid, large list of email addresses is the critical factor.’ He also points to the importance of a pre-launch website, an ‘online place where people interested in the book’s subject matter congregate’. His website for the Kahn book was launched six months ahead of the launch. He also puts great emphasis on identifying ‘each and every nook and cranny’ of the potential readership.

Lucie Parker, associate publisher at San Francisco’s Letterform Archive (see Eye 100), describes crowdfunding as ‘a dynamic, ever-shifting landscape, and one that confounds a single best strategy.’ The Archive, founded by Rob Saunders in 2015, has so far published three books: works about W. A. Dwiggins, Jennifer Morla and Jack Stauffacher, and plans many more, including a new monograph on Amos Paul Kennedy Jr. and Kelli Anderson’s Alphabet in Motion: A Pop-Up Book for Typophiles.

Spread from Bruce Kennett’s crowdfunded W. A. Dwigins: A Life in Design (Letterform Archive), showing archive photos, drawings, beer labels (left) and hand-lettered artwork for a 1936 S. D. Warren brochure (right).

Spread from Alfa-Beta: lo studio e il disegno del carattere (2020) in the sub-chapter entitled ‘Caratteri ornati del ’900’ [‘20th-Century ornate typefaces’]. Novarese writes: ‘even ornate typefaces and their motifs … have grown more reasonable … they arouse interest without resorting to aesthetic shock tactics.’

The revival edition of Aldo Novarese’s Alfa-Beta: lo studio e il disegno del carattere (2020) excited much interest and nearly doubled its €30,000 goal in September 2020. Publisher Archivio Tipografico offered incentives that ranged from €5 for a thank-you email to €560 (or more) for an original acrylic painting by Novarese alongside a slipcased ‘Deluxe’ edition, with a numbered, limited-edition letterpress specimen and a Reader’s Guide. In between lay the options of a €65 hardback and a €100 Deluxe version. The list of supporters reads like a typographic Who’s Who.

I ask Letterform Archive’s Parker whether it was important to have an element of surprise in order to excite and energise supporters. ‘As in trade publishing, the secret sauce has at least one not so very secret ingredient,’ replies Parker. ‘Make sure an author’s fans know something good is coming so they can be ready to support it … but maintain enough mystery so they can be delighted and surprised – not already tired of it – when it is time to act.’ Parker explains that Anderson has been sharing her prototyping process with her 84,000-plus Instagram followers so they can feel invested in the book’s story. ‘But we won’t be revealing fully designed interiors until we launch Alphabet in Motion,’ says Parker.

‘You need a “hero” you can build a story around,’ says David Jenkins (Circa Press). ‘I don’t think it would work for architecture books – unless you can find me a cult figure – and I wouldn’t try it for general surveys in other fields.’ For Circa’s crowdfunded Tat* – Inspirational Graphic Ephemera, the ‘hero’ is Andy Altmann, who recently closed down Why Not? Associates, the graphic design practice he founded with David Ellis and Howard Greenhalgh. Altmann’s collection of printed ephemera – including tickets, price labels and torn posters – has attracted enthusiastic support (£11,615 of a £10,000 goal) from fellow designers who recognise the DNA that Tat* shares with Why Not? projects such as the Blackpool Comedy Carpet (see ‘Gag pile’ on the Eye blog).

Sometimes the ‘hero’ is the book itself. When Jan Middendorp decided to reprint his acclaimed Dutch Type, he knew there was a demand for it – copies of the original 2004 edition were fetching outrageous sums on the secondhand market and he wished to make it available to new readers. He collected mailing lists at type conferences and used modest advertising and social media to run a campaign that benefited from the support of admirers such as Erik Spiekermann, who tweeted enthusiastically about the book. Although Middendorp is acutely aware of the downsides of running a one-man publishing house (including the escalating costs of distribution and storage), he notes that self-publishing a reprint, financed by a crowdfunding campaign, gave him control of the book’s printing quality, binding and cover design that would have been more difficult with a conventional publisher.

Wallace Henning discovered many things from publishing the facsimile British Rail Manual (2017), not least that he had to learn how to run a business the hard way. However, he was gratified to discover that readers will support passion projects: ‘Your supporters really do support you. There are some grumpy people who will give you a hard time, but ultimately everyone is behind you, and you need to remember this. As long as you keep everyone updated and show the love that you’re putting into it.’

Another publishing venture with a devoted following is The Gentle Author’s Spitalfields Life Books. Its output includes A Modest Living, Memoirs Of A Cockney Sikh, the paintings of East End Vernacular and photography books such as Spitalfields Nippers. ‘Every book has been crowdfunded,’ the anonymous Author told me. ‘I expected it to get harder but we have acquired more supporters and a growing reputation. We only ask the readers to help us publish a book if we already know from the readership numbers that it is viable. That said, we have to announce and pre-sell a book before we crowdfund it, so we skate on thin ice every time.’

The ‘thin ice’ alluded to by the Gentle Author affects every aspect of making a book. Unit’s Finegan points out how much has to be done before presenting the project to its potential readership. In addition to devising special editions, extras and ingenious incentives, she says, ‘you have to make sure your author is on board, your designers are on board, you have permission. You have to do everything apart from making the book. You can’t go into it with a vanilla project. There has to be a conviction that it will happen.’ She cites the dedication shown by Mark Holt with Munich ’72, his comprehensive book about the design and identity for the 1972 Olympics (discussed overleaf and reviewed on page 110).

Not every project works, and getting the timing right is another challenge. Dan Adams and his colleagues from the 1980s/90s skateboarding magazine Read and Destroy (RaD) invested a lot of time in planning a lavish book that would bring together powerful photography from the title. They worked hard on the preparation for the book design and made videos designed to reach their potential audience. For Adams, the benefits of Kickstarter were clear: ‘It allowed us to make the book we wanted to make, without a publisher’s restrictions.’ He was impressed by the extent to which Kickstarter were prepared to help: ‘Kickstarter was amazingly supportive and gave a lot of advice while the campaign was running.’ However RaD never hit its target.

Adams muses on the factors that may have prevented the campaign working: ‘Our audience is very engaged, but the idea of paying a lot of money for a book is still a stretch. I think with hindsight we over-cooked it.’ Skate books, he says, tend to have lower price points; the RaD book was conceived as a substantial double volume with a level of photographic reproduction and printing that would redress the production limitations of the original magazine three decades ago. After the crowdfunder ended, Kickstarter advised Adams and his colleagues how they could organise a re-run with more success given the project’s highly engaged following.

Unit’s Finegan knows all too well that ‘you can have a favourite project that doesn’t happen.’ She recalls a strong feeling within Unit that Will Burtin (see Eye 82) was a designer that deserved recognition for his body of work. ‘We put a lot of effort into that, and it just didn’t fly.’ By contrast, A-Z of The Designers Republic™ (2019) raised more than one-and-a-half times the target set.

Many of the people I talked to found the process of sending out books particularly stressful, citing uncertainty about mailing costs, which in the UK are due to rise steeply with the malign effects of leaving the European Union’s single market. Dan Adams said: ‘You have to become quite a sophisticated shipping operation,’ echoing the experiences of many other crowdfunding teams. ‘If it’s too big, it’ll be too heavy to ship economically. If you want to do a global product, it has to be competitively priced for the world.’ Finegan is conscious of the importance of packaging that protects the books, taking trouble to see that each book is packed up with protective corners between layers of sturdy cardboard. ‘A book is not just content, it’s an object,’ she says. ‘We’re responsible for even the smallest mark or scratch and we know our audience will send the books back if they aren’t perfect.’ Postage and packaging costs can mushroom in the time between funding and fulfilment, and crowdfunding publishers need to be aware that the platform takes a substantial cut – five per cent plus payment processing fees between three and five per cent in the case of Kickstarter in the UK.

Everyone I contacted cited Hamish Smyth and Jesse Reed’s 1970 NYC Transit Authority Graphics Standards Manual (2014) as the ‘gold standard’ of crowdfunded design books. The book overshot its original target of $108,000 to hit an eye-watering $802,812. Kickstarter’s Atwell notes the way Smyth and Reed reached ‘a broad community of backers and even people who might not have thought of themselves as design book aficionados.’

If there is a thread that connects such different crowdfunded books, it is the way a book’s potential purchaser values the specialness of the book and its accompanying ‘rewards’. These may be as little as the thrill of seeing their name in the list of supporters, or as substantial as a signed, limited-edition print. Illustrator Mr Bingo promised an alcohol-fuelled train journey as an incentive to crowdfund Hate Mail (which hit its target within nine hours), while the more self-effacing Gentle Author has provided sumptuous dinners. The Author has never used a crowdfunding platform: ‘I simply ask people to write in if they would like to support the publication,’ he says.

Designer and artist Sam Winston was helped by a fan base that straddles both art and design. Winston explains that Covid-19 ‘created a window’ through which he could revisit his acclaimed A Dictionary Story, including a letterpress edition made with Nomad Press. ‘I had a few options, deciding if I wanted to take this to a mainstream publisher or more limited-edition artist’s books. I used Kickstarter in part to find out where most of my support comes from – the mass-produced books or small (limited-run) artworks.’ Winston’s careful preparation, together with a wide variety of editions and rewards and a promotional short directed by Ed Prosser led to a campaign that hit its £8000 target within 24 hours and raised £21,101 by the deadline.

He went on to make an additional 50 per cent from after-sales. Henning realised the value of such sales quite late. ‘You need to have something set up to capture the people who missed the crowdfunder, and be ready right away to ride the hype and get more orders.’

Inque, the new annual, advertising-free magazine devised by Port founders Dan Crowe and Matt Willey, was a tough sell, with a high target (£150,000) that raised eyebrows. It sailed across the finishing line with a few days to go, eventually raising £178,248 – not bad for a title that will not publish its tenth and final edition until 2031. As always, it is all about hope, faith and money. Yet Kickstarter, for all its influence on current publishing, is neither store nor publisher. As they repeatedly remind us: ‘We don’t guarantee projects or investigate a creator’s ability to complete them. It’s the responsibility of the creator to complete their project as promised, and the claims of the project are theirs alone.’

Spread from Munich ’72: The Visual Output of Otl Aicher’s Dept XI (2019), designed and edited by Mark Holt.

Right. Michael Burke’s event posters. Holt writes: ‘Burke’s recollection of these posters is that Otl Aicher had no knowledge of the request and only saw them after they were completed.

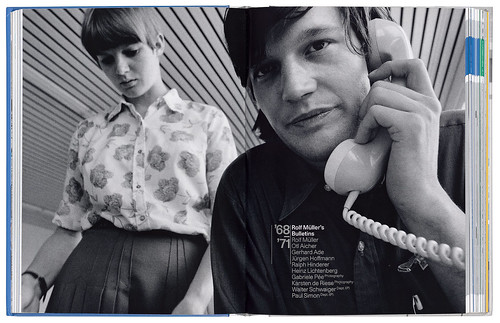

Spread from Munich ’72. Photograph by Karsten de Riese of Elena Winschermann (left), who designed the Waldi dog mascot, and Rolf Müller, deputy to design director Otl Aicher.

John L. Walters, editor of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 101 vol. 26, 2021

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.

Links

See also ‘Mark Holt: Games, set and dispatch’

Unit Editions

Circa Press

Volume

Designers & Books

Letterform Archive

Archivio Tipografico

Jan Middendorp – Dutch Type

Sam Winston

Wallace Henning – British Rail Manual

Mark Holt – Munich ’72

Read and Destroy Magazine

Hamish Smyth and Jesse Reed – 1970 NYC Transit Authority Graphics Standards Manual

Nomad Press

Mr. Bingo – Hate Mail

Inque Magazine