Winter 2007

Fair trade?

Indian advertising has a not-so-hidden message: change your skin colour to get the perfect job or mate

Television audiences in India didn’t get a chance to view the excellent ‘Dove: Evolution’ campaign by Ogilvy and Mather, Toronto, for its Anglo-Dutch corporate client Unilever. In its ‘Campaign for Real Beauty’, Unilever took the radical step of challenging the standard beauty industry practice of professional make-over, photography and sophisticated digital retouching to morph the girl next door into a supermodel fit to be on giant billboards.

Strangely enough, this feelgood message directed mainly at the fair maidens of North America and Europe is conspicuous by its absence in the dark-brown-skinned media markets of South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. In sharp contrast to the Dove advertisements are the ads for Fair & Lovely, Hindustan Unilever’s ‘World’s No. 1 Total Fairness Cream’ – reportedly, a goldmine the R&D team struck when developing a tanning cream for the Western market. Since its invention in the 1970s it has been sold in 40 countries, possibly holding the dubious distinction of being the most exported indigenously developed brand from India. Not just the product; the commercials as well, with minor variations on the original, which was crafted by the highly respected Alyque Padamsee while acting as a consultant to Lintas (now Lowe) in Mumbai, India’s ad and film capital.

The Fair & Lovely campaign has had a rich tradition of featuring ads that are nothing short of degrading: some of the most offensive were belatedly pulled off the air due to protests by Indian women’s organisations. The campaign adopts an easy-to-understand, unambiguously racist narrative: a young woman is rejected in a job interview, uses Fair & Lovely Total Whiteness Cream, her skin becomes ‘three shades lighter’ on the ‘Fairness Meter’ in just four weeks, and lands the same job based on her ‘new’ credentials. The frequency of the ads is high in South Indian markets where there is a high percentage of darker-skinned Indians. It should be admitted, however, that the cream has nourishing vitamins and does not contain harmful bleaching agents. It even comes with a money-back guarantee!

Myths of fairness

The success of the product has spawned many wannabee brands – now aimed both at women and men – all trying to carve a little off the 60 per cent market share that F&L holds. Interestingly, Alyque Padamsee was involved in Emami’s ‘Fair and Handsome’ cream for men, which is now touted as the ‘world’s No. 1 fairness cream FOR MEN’.

The phenomenal success of fairness creams is fundamentally a reflection of a society that has had a racist foundation since the Pre-Vedic, Pre-Aryan periods. Being born into the lighter varna (which simply means ‘colour’ in Sanskrit) automatically granted one higher social status for centuries. Lighter skin denoted not just high social status, but a higher spiritual space as well. [...]

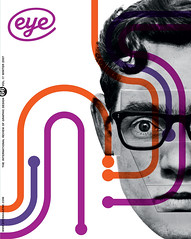

First published in Eye no. 66 vol. 17 2007

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.