Winter 2014

Trust me, I’m a photographer

Trepat: A Case Study in Avant-Garde Photography

By Joan Fontcuberta<br> Éditions Bessard, €60, hardback<br>Joan Fontcuberta: Stranger than Fiction

Curated by Greg Hobson<br> Science Museum, London, 23 July–9 November 2014<br>The Photography of Nature / The Nature of Photography

By Joan Fontcuberta with essays by Geoffrey Batchen and Jorge Wagensberg<br> Mack, £55, hardback<br>Pandora’s Camera

By Joan Fontcuberta<br> Mack, £15, paperback<br>

I’m familiar with Joan Fontcuberta’s work, so I should have known better. The Spanish photographer is renowned for projects that question our willingness to believe that what we see in photographs must be true. Even so, when I walked into Fontcuberta’s exhibition, ‘Trepat: A Case Study in Avant-Garde Photography’ (shown at the annual Les Rencontres d’Arles festival in 2014), my initial reaction, for a minute or two, was that this time he appeared to be working as a more conventional curator. I had never heard of Trepat, a Spanish manufacturer of machinery and farm equipment, or its activities in the 1920s. It seemed plausible that its founder, Josep Trepat Galceran, might have sought the collaboration of Modernist photographers famous for their commitment to a machine aesthetic.

The exhibition was largely captionless and unfortunately, according to the attendant, the handouts stored in a box on the wall near the entrance had run out. That seemed curious, to say the least, since the exhibition was in a major city gallery. The walls were covered with old photographs of machinery and a few paintings, and every so often there was a picture appearing to show that figures such as Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy had paid visits to the Trepat factory. But I knew the original images and it was clear that the industrial settings they seemed to document had been added to the pictures. When pressed a little harder, the attendant admitted that there never had been any handout sheets with captions and that this investigation of art and industry in prewar Spain was, as I suspected by then, another elaborately conceived Fontcuberta hoax.

The Trepat show is bound to travel, like all Fontcuberta’s installations, and in the meantime there is an artist’s book of the project from which the caption pages have been roughly torn, as if a production mishap has occurred. The book reproduces the appeal of the exhibition. Monochrome photographs of machines have great formal power and many Modernists made visual documents of industrial scenes and objects. Fontcuberta’s illusion is so seductive because it hinges on a well established narrative of twentieth-century art in relation to the ‘machine age’ and purports to furnish new and unfamiliar information to support it. As curator, he provides everything that is needed to encourage a leap of faith and an acceptance of historical ‘evidence’ that appeared, in Arles, to be endorsed by a reputable institution.

This institutional authority is what made the Media Space at the Science Museum such an appropriate venue for Fontcuberta’s first major retrospective in Britain. It must be the case now that any exhibition of his work in an art gallery is likely to attract audiences with some degree of familiarity with his curatorial subversions. In a museum of science that is hugely popular with the general public, and especially with families, there is a greater chance that people will enter the exhibition without any prior knowledge of the artist or his intentions.

Professor Peter Ameisenhaufen and Centaurus neandertalensis, from the Science Museum exhibition ‘Stranger than Fiction’.

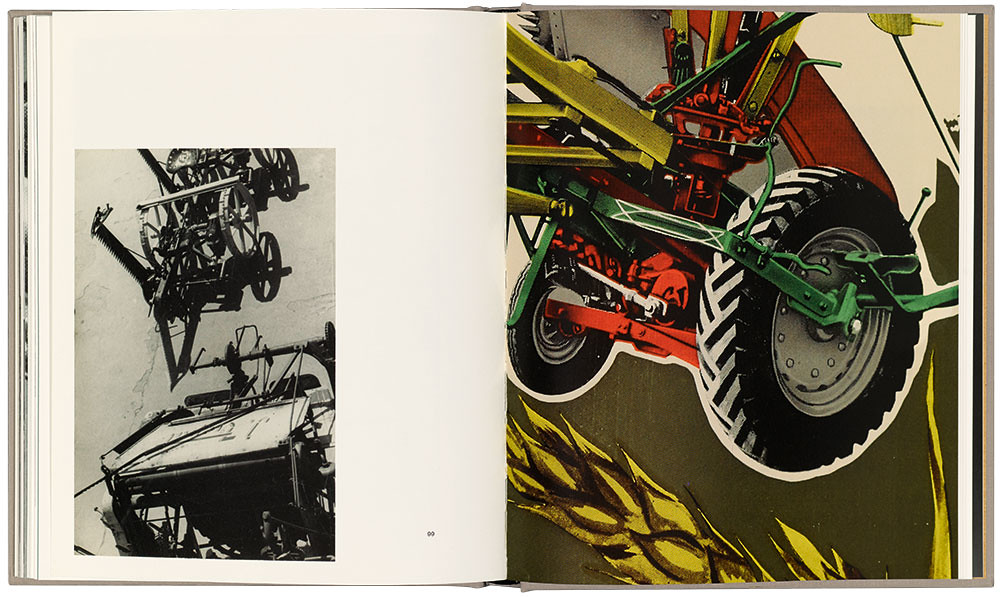

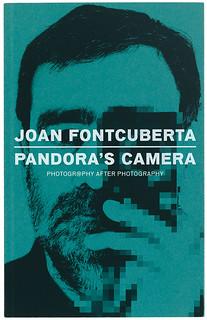

Top: Spread from Joan Fontcuberta’s Trepat.

‘Stranger than Fiction’ presented six of Fontcuberta’s projects, opening with ‘Fauna’, his 1987 collaboration with the late Pere Formiguera, which was my own introduction to Fontcuberta in Barcelona around that time. The project shows peculiar animals, previously unknown to science, discovered by a fictitious researcher named Professor Peter Ameisenhaufen. The meticulously faked collection of notebook pages, drawings, photographs and life-like models of these improbable beasts has lost none of its impact. Photographs of Ameisenhaufen interacting in the wild with the Centaurus neandertalensis, a cross between a baboon and a deer, are surprisingly convincing, even for a doubter. As contributor Geoffrey Batchen notes in The Photography of Nature / The Nature of Photography (2013), Fontcuberta ‘exploits our desire to believe what we see in a photograph, whatever the truth of the matter’.

The Science Museum’s explanatory panels kept a straight face and preserved the illusion; only in the accompanying booklet were the fabrications revealed. If we start from the premise, as Fontcuberta does, that every photograph is faked in some way, then the emphasis shifts from the putative hoax (falling for it; exposing it) to philosophical reflection on why we are so inclined to place our trust in pictures in spite of the continuous evidence of their untrustworthiness. Batchen suggests that our faith in photography as a means of preserving traces of what once existed comes, at root, from our desire to stop time and deny the possibility of death. With so much at stake, we find it impossible to give up on the medium.

Be that as it may, Fontcuberta is an ingenious artificer, who can turn mosquito splats on a speeding car’s windscreen into pictorial visions of distant constellations, and his most beguiling weapon is surely his sense of humour. In ‘Karelia, Miracles & Co’ (2002), he poses as a novice to enter a monastery in Karelia in Finland where monks are allegedly taught to perform miracles. In a series of pictures, the bearded initiate levitates, grows breasts, surfs on the back of a dolphin, and teaches a gang of meerkats to read epic poetry. A naturally likeable and amusing performer, Fontcuberta delivers the project with a big wink to the viewer, and the Science Museum visitors I saw looked like they were greatly appreciating the joke.

This is how I prefer to take Fontcuberta, not as a demystifier showing us the error of our ways, but as a very smart fabulist who plays with our awareness of the compromised nature of photography. There can’t be many people today, after all, who haven’t grasped that you can do whatever you like to a digital picture. Photography has been transforming itself into new types of practice ever since the medium began to go digital in the 1990s. In an essay wryly titled ‘I Knew the Spice Girls’, in Pandora’s Camera, a new collection, Fontcuberta proposes that the era of film-based photography was a kind of aberration, ‘an accident of history’, and that digital photography is much closer in nature to writing or painting, since it is constructed from graphic units, in a grid of pixels, each one of which can be worked on individually. Analogue photography may have its origins in the idea of objective documentation of something that happened, but a digital image, like a painted image, is essentially a constructed image. Not only does Fontcuberta brilliantly exploit the photographic image as a medium of criticism in project after project, but he also turns out, in these valuable essays, to be a writer and critic of great insight, eloquence and humour.

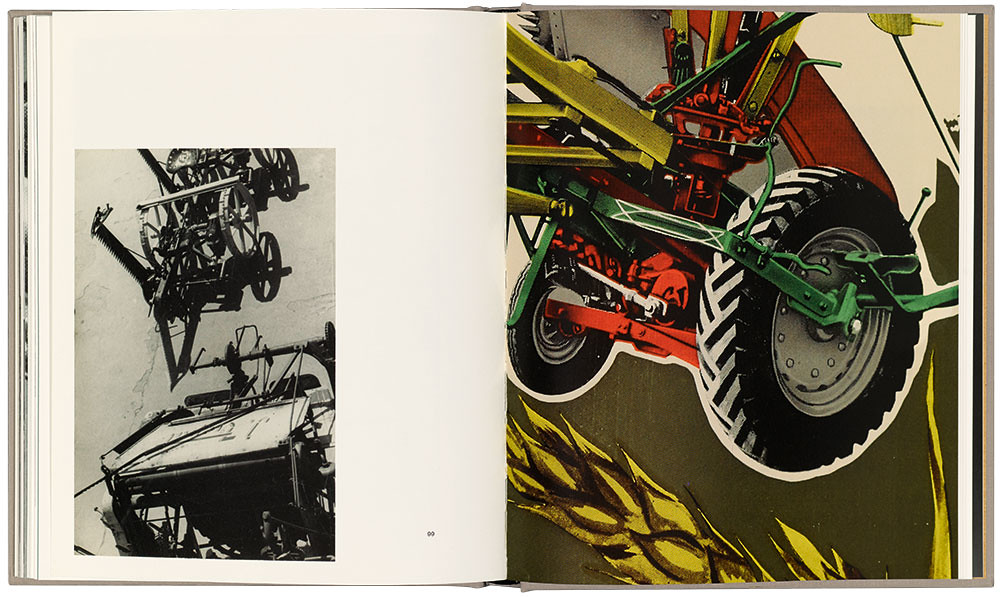

Cover of Joan Fontcuberta’s Trepat: A Case Study in Avant-Garde Photography, with tipped-in print, made in an edition of 350.

Top: Spread from Joan Fontcuberta’s Trepat.

Pandora’s Camera. Design: Grégoire Pujade-Lauraine and Edith Bazin.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no. 89 vol. 23 2014

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 89 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.